During a recent appearance on Conan O’Brien’s podcast, Smashing Pumpkins lead singer Billy Corgan offered a gloomy prediction for the future of music. He said that once kids get their hands on AI as a songwriting tool, that’ll be the end of the process of organic songwriting.

“If you’re 15 and you have to spend 10,000 hours listening to The Beatles and Joy Division to learn how to write a song, versus you can punch a button and it’s going to give you seven options … it’s over,” Corgan said.

Barely missing a beat, Paul McCartney now says even he is using AI to make one last Beatles song, with plans to release a track later this year featuring John Lennon’s voice.

The rapid rise of generative AI technology and tools such as ChatGPT, and the legal and ethical arguments for how they will be used to manipulate and create content, is being debated in numerous corners of society.

In music circles, there’s a mix of enthusiasm about AI, including from artists such as Grimes, who is inviting fans to make songs with her AI-generated voice and split any royalties. And there’s trepidation, as with Corgan, and others, such as Sting, who told the BBC that the “building blocks of music belong to human beings.”

The topic can be a bit like music itself — subjective.

GeekWire reached out to a variety of artists and professionals from Seattle’s music scene to hear how the prospect of AI is being received in the community, who might want to use it, and what the future might hold for songwriters, producers, label execs, DJs and others. Keep reading for their insights.

Danny Newcomb, musician, songwriter and startup CEO

- Danny Newcomb has played in Seattle bands including Shadow, Goodness, The Rockfords and Sugarmakers. He’s the founder and CEO of a new AI company for sync music licensing called Incantio.

Danny Newcomb admits “sync licensing” doesn’t sound particularly sexy. But independent artists should be excited nonetheless by the new AI platform he is building in Seattle to better match music with moving images in TV, movies, advertising and elsewhere.

The two-sided business platform, called Incantio, allows artists to upload their music into discovery pools and set pricing, and it allows creators to more easily find that music through recommendations related to mood, tempo, vocals, etc.

‘I haven’t heard anything that doesn’t sound like wet cardboard.’

“AI can curate all this music and extract data from it,” Newcomb said. “We’re basically creating a tube or a funnel where all the music comes in one side and then is recommended on the other side by extracting the same features.”

In Newcomb’s view, AI’s ability to see patterns over vast amounts of data that no human wants to sort through is the best use for the technology, and the value of his startup. Generative AI, on the other hand, in which software can be used to write lyrics or replicate vocals, is less enticing to Newcomb

“I like to work and I like to push myself. So if you’re going to take all that out of the equation … I don’t know,” he said.

Newcomb figures AI will provide other options beyond the mechanical means of reproducing music. Artists might use voice commands to augment and speed the process, such as “Give me an ending” or “I’m hearing a melody like this, can you put this in the flavor of piano?”

“I haven’t heard anything that doesn’t sound like wet cardboard,” Newcomb said. “You might be able to underscore something in a weird Czechoslovakian vampire movie, but I don’t think it’s going to be front and center, and it’s not going to be the next Jon Bon Jovi.”

Eva Walker, musician and DJ

- Eva Walker is a DJ with Seattle radio station KEXP, where she hosts the local music show Audioasis. She’s also a member of the rock band The Black Tones.

Making music in her band and playing music on the radio is a distinctly human experience for Eva Walker.

The Seattle musician and DJ hears from artists in the community who are scared about what AI will do to the creative economy and others who are open to the tech as a useful tool. When it comes to writing songs, a bot can’t write Walker’s story.

She dabbled once in ChatGPT to write a song, and the end result was “not very interesting at all.”

‘That’s what’s so great about human-powered radio. I’m doing all the coding.’

“It has to come from my life, my experiences, the things I’ve been around, which is one story of billions of other stories,” Walker said. “It’s unique, and I like writing about that.”

Her views transfer to her time on the radio, when she’s selecting songs based on her own human emotion or that of her listeners, giving people a reason to tune into KEXP rather than press play on a Spotify playlist. She said when she finds a way to segue from John Coltrane to the Melvins, it’s based on an inherent feeling.

“The human me is the only me I know,” Walker said. “An AI bot and its algorithms may never make that connection. That’s what’s so great about human-powered radio. I’m doing all the coding.”

But she’s open to listening to anything — bot or not.

“Can a human use AI to create something beautiful? Yeah, probably,” she said. “If it’s beautiful, I’ll say it’s beautiful. I’ll probably be more impressed if it’s something that was completely made from scratch, but I could still enjoy it if it’s AI.”

And she appreciates the possibilities that AI opens up when it comes to accessibility.

“Everyone should be able to create and not everyone can play an instrument,” she said.

Steve Fisk, musician and producer

- Steve Fisk is a longtime Pacific Northwest audio engineer and record producer who worked with such bands as Soundgarden and Screaming Trees. He was a member of the 1990s electro-funk soul duo Pigeonhed.

Steve Fisk has witnessed music hype of epic proportions from the frontlines of Seattle’s early ’90s grunge explosion. He’s not worried about music robots. And he’s not mincing words — or using ChatGPT to craft them.

“We’re in the dawn of this kind of horsesh*t,” Fisk said. “The kind of people that can be fooled by AI are the kind of people that also go into the tar pit because they think there’s something in there to eat and they get stuck. AI might actually thin the herd a little bit. If you’re dumb enough to fall for this sh*t, maybe there’s not a place for you in the future.”

‘I don’t think there’s going to be a bunch of AI Biggie fans 20 years from now.’

Admittedly old fashioned and “a little jaded,” Fisk is not averse to technology. In fact, he’s using a cutting edge audio platform in work he’s doing at Redmond, Wash.-based Immersion Networks, which uses software and hardware to “improve the human listening experience.”

But he thinks musicians and songwriters have managed this long without AI, and the mechanical methods they do use still rely on human interaction.

“A rhythm machine isn’t a bot and it’s very useful,” Fisk said. “It comes pre-programmed with some beats and those beats have become part of our culture. It’s artificial and all of that, but it was completely driven by the people that built a machine and the people that use the machine — there’s nothing smart in there.”

Fisk, who worked with Kurt Cobain, Chris Cornell and Mark Lanegan, is also not interested in having AI recreate the voice of any artist who is no longer alive, like the plan by producer Timbaland to use AI voice filters to give life after death to stars such as Biggie Smalls.

“The fact is I’m sick of hearing their voice because they’ve been celebrated like Jesus Christ. I don’t want to hear ‘All Apologies’ one more time, thank you,” Fisk said, referencing a Nirvana song. “I don’t think that idea is gonna last. I don’t think there’s going to be a bunch of AI Biggie fans 20 years from now.”

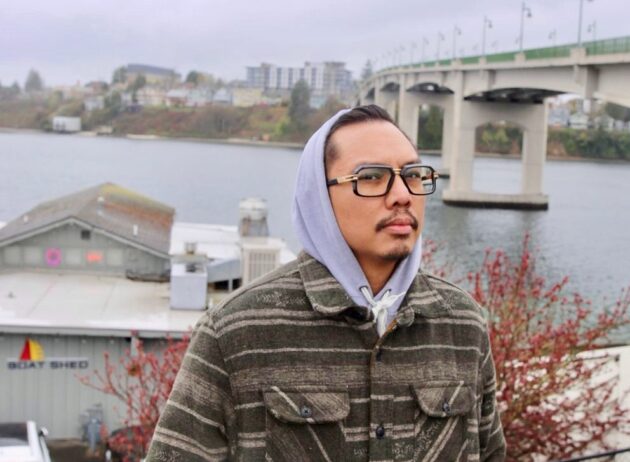

Geo Quibuyen, rapper, writer and business owner

- Geo Quibuyen is a member of the Seattle hip-hop duo Blue Scholars, co-owner of Hood Famous Bakeshop, and the creative mind behind the Substack newsletter Brownouts.

AI technology may not change the way music sounds to some people, but Geo Quibuyen thinks it’s definitely poised to shift the way many artists make music. As a longtime musician with strong roots in Seattle’s hip-hop scene, Quibuyen has seen technology change music production and consumption several times over.

“Although the tech changes the forms, our relationship to music and the many ways we interact with it to enrich our lives remains,” Quibuyen said, stressing that there are plenty of holdovers from previous-era tech and a new generation foregoing the latest trends to explore analog production.

“If AI does change anything significant, it won’t be because of the tech itself but because of something moving and interesting generated by the artists and audiences that bring music to life,” he said.

‘It’s wild to imagine, if this is just the beginning, what this could look like later on.’

Quibuyen has tried a few different prompts in ChatGPT while writing lyrics and he’s come away finding the results more amusing than useful. He likens celebrity voice mimicry to the fun that Photoshopping faces provided 20 years ago.

“It’s wild to imagine, if this is just the beginning, what this could look like later on,” Quibuyen said. “Right now, it’s still in its novelty phase so what seems impressive now will eventually become commonplace at the rate things are moving.”

But music is fairly low among his list of mediums and markets that he’s concerned about when it comes to AI’s potential impact. As with all technology, he worries about how AI might reinforce inequalities and bring disproportionate harm to communities.

“I’m definitely not on the doomsayer bandwagon,” he said. “I’m both skeptical of the hype and intrigued by the possibilities, but more so in society in general: in the media (of which music is a part), in economics and finance, in housing and job markets, in city planning, in policing.”

Sera Cahoone, songwriter and musician

- Sera Cahoone is a Seattle singer/songwriter who has released four albums since 2006. She previously played drums in the bands Carrisa’s Wierd and Band of Horses.

Sera Cahoone is not a techie. The singer/songwriter uses Pro Tools music creation and production software a bit, and other recording tools at home.

“It’s definitely not anything too technical, because it hurts my brain,” she laughed.

But AI has sparked Cahoone’s curiosity, if only because she wants to be knowledgeable about it and be able to carry on conversations with fellow artists about how they might be impacted by rapid changes in their industry.

‘After a while people are gonna be bored of it because it’s going to be obvious who writes songs with AI.’

“I’ve heard you can put in whatever you want to write a song about, all the words, and then it will pop out, lyrically, a song,” she said. “To me I’m like, great, because I f**king hate writing lyrics.”

She gave it a try when she asked ChatGPT to write a song about her dog, who passed away five years ago. The result was “hilarious,” but she called the process of letting AI take over that work “insane.”

She wonders whether it will affect the authenticity of musicians and music, or whether it will just make all of us musicians if we want to push the right buttons.

“After a while people are gonna figure that out, they’re gonna be bored of it because it’s going to be obvious who writes songs with AI,” Cahoone said.

Asked if she was currently working on any new music or another record, she sighed.

“Yeah, it’s slow moving,” she said.

She laughed again when told there was a new way to speed that process.

Tony Kiewel, record label executive

- Tony Kiewel is the co-president of Seattle record label Sub Pop, where he’s worked for 23 years. He’s on the boards of independent-music-focused A2IM and WIN.

When Tony Kiewel thinks about a hot artist on Sub Pop these days, whether it’s Suki Waterhouse or Bully or someone else, he’s less concerned that they’d use AI to create their music than he is about how their music will find listeners in a marketplace overcrowded with meaningless bot tracks.

“When a lot of people imagine some of the immediate ramifications of AI in the music business side, they’re less concerned about ‘fake Drake’ than they are about how you could just push a button on a website, put in your credit card, and just create, create, create, create, create thousands of tracks,” Kiewel said.

‘I asked it about me, and it said that I used to be in a band I was never in. It’s still pretty stupid.’

He referenced the controversy around music creation app Boomy, which has created millions of tracks and been accused by Spotify of “stream manipulation.”

The fear that digital service providers such as Spotify, Pandora, Apple Music and others would lead to the demise of independent record labels and artists has been replaced by a fear that AI content will flood those services.

That’s not a problem caused by AI, which Kiewel calls another tool, a better version of things that musicians have been using for for decades, like using samba on your Casio.

“We could argue whether drum machines are already too much AI, or vocoders,” he said. “These problems are actually people acting in their own interests, some perhaps on a sociopathic level, some just on a capitalist agenda.”

Like others, Kiewel has played around in ChatGPT. He asked the program to name the top 20 records of 2020. It knew. He asked what key the top 20 records were in. It knew. He asked for the beats per minute of all of those songs and it knew.

“It sure knows an awful lot, or thinks it knows an awful lot, about these songs,” he said. “I also asked it about me, and it said that I used to be in a band I was never in. It’s still pretty stupid.”