As swaths of wildlands are being scorched and communities smoked out by another unusually hot, dry summer, researchers in Washington state say there could be a less miserable, environmentally beneficial alternative.

A key part of the solution is allowing some smaller wildfires to burn when conditions are favorable and by conducting prescribed burns — an approach historically practiced by indigenous people in North America.

“We can still maintain forests and live with fire,” said Susan Prichard, a research scientist with the University of Washington’s School of Environmental and Forest Sciences. “There is a better way forward. And the way I know that is indigenous people throughout this continent have, and still do, live with fire.”

Over the past nine years, Prichard and colleagues developed a model called REBURN to help simulate and visualize the impacts of different wildfire management strategies to explore how the forests and fires would respond on a landscape-wide scale.

The researchers began delving into the issue following the 2006 Tripod Complex fire, a blaze in north central Washington that charred 175,000 acres, an area more than three times the size of Seattle. Megafires like this were rare in the past, and Prichard expected it to be the biggest fire of her career. But even more massive fires followed as the planet has continued warming due to climate change.

Firefighters battling blazes in forests typically don’t put them out with water and fire retardants like you do when a building is on fire. Instead they try to contain them by using bulldozers, shovels and other tools to create fuel-free “fences” around the fires and letting them burn themselves out.

Megafires are difficult to control. They’ll kill most or all of the trees in an area, eliminating the source of new seeds that spur recovery. And young trees that do take hold can struggle thanks to climatic shift to longer droughts.

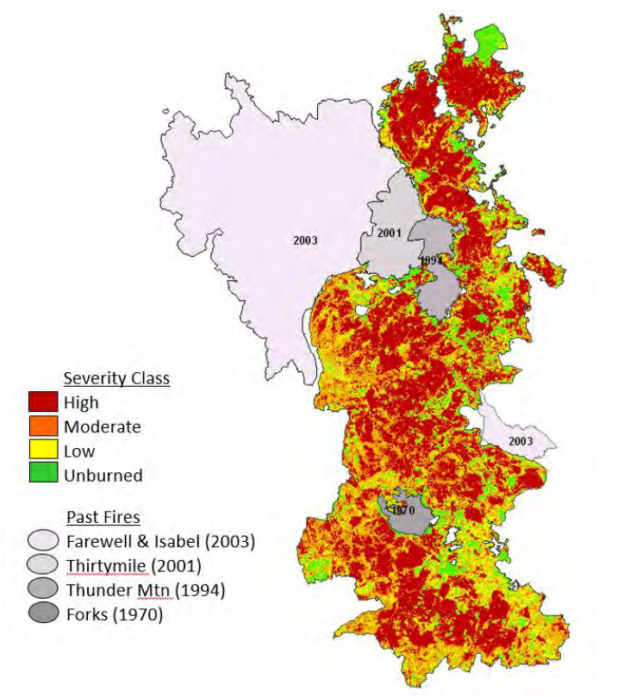

Prichard and her colleagues — Paul Hessburg, Nicholas Povak and Brion Salter of the U.S. Forest Service’s Pacific Northwest Research Station and consulting fire ecologist Robert Gray — found that aggressive fire suppression over decades created uniform forest conditions with dense trees with thick understory shrubs and grasses. It’s the sort of conditions that stoked the Tripod Complex, igniting the tree canopy and scorching ponderosa pines and Douglas fir, as well as higher elevation spruce, fir and pine species.

The researchers used the REBURN model to imagine a different outcome. They found that allowing smaller fires results in mosaics of forest of varying age and available fuel. When a landscape is 35 to 50% previously burned fence areas, it rarely experiences large fire years, according to the model.

“What we found out is the secret sauce in fire on the landscape is reburning,” said Hessburg, a senior research ecologist with the Forest Service. “It’s not just fire, it’s fire-on-fire interactions.”

Allowing an area to burn, and then burn again, helps create a patchwork of forest landscapes with less flammable material. That includes sparsely and heavily treed areas, meadows and grasslands and shrubs, which creates a more stable condition that hems in blazes. It also provides different kinds of habitat for wildlife such as lynx, deer, snowshoe hares, moose and other creatures.

The team published articles in June and July in the journal Fire Ecology about forest management insights from the REBURN model.

‘Fire is a blunt management tool. So we’d have to be brave.’

– Susan Prichard, UW School of Environmental and Forest Sciences

There’s strong evidence for indigenous people employing the management strategy of controlled burns. Oral histories tell of the practice, and there are stories revealed by the trees themselves. Fires create scars that are embedded in a tree’s rings, and researchers have built a database cataloguing fire scars. They can determine the severity of past fires and if trees burned in spring or fall, outside of the lightning season and likely intentionally set by humans.

Prescribed burns are smaller and less intense events, cleaning out the understory fuels and providing a “bath by fire,” as Prichard described it.

If smaller controlled fires are allowed, Prichard said, “we’re going eventually to get to the point where wildfires emit less smoke. It’s very hard to imagine right now. But it is a reality that over time, these fuels are going to be chipped away.”

The team is now adapting the REBURN model to match the conditions in southern British Columbia and northern California to provide insights for managers in those areas.

Hessburg emphasized the importance of communities that live in at-risk areas taking steps to safeguard their properties. That includes removing fuel near homes and using fire-resistant building materials. Government agencies are likewise working to thin out dense forests where fires have been prevented.

Already this year, nearly 37,000 U.S. wildfires have burned 1,800,272 acres — including fires that killed more than 100 people on Maui and leveled most of the historic town of Lahaina. There are currently 69 active fires in the U.S., according to the National Interagency Fire Center. Four are contained.

But while the REBURN model and other research demonstrate the benefits of fighting fire with fire, the question is whether forest managers and communities will accept it.

“Fire is a blunt management tool,” Prichard said. “So we’d have to be brave.”